-

-

"What is contemporary art?"

“Contemporary art” may not have one single meaning: SEA (Socially Engaged Art) is, for example, completely different from NFTs, or from the works lining the walls of art fairs. It would not be an exaggeration to say that we are only running in circles every time we ask the question “what is contemporary art?”.

I have accordingly shied away from contemporary art as a whole, focusing my work rather on post-war avant-garde art and art criticism, and on the unique Japanese art scene.

Since around 2019, however, I began to feel the limits of this approach. The reason why I felt limited was not because of the problem of art criticism tied to literature, which is peculiar to Japan, concerning words and definitions such as whether "art" should be called "art" or not, but rather something more serious. I had lost sight of what to do with art. Since then, I have become absorbed in ceramics in order to forget about all that was going on in the art world. There was no particular reason for me to gravitate towards ceramics, but it was ultimately a turning point.

It is well-known that the concept of “art” was imported to Japan at the end of the 19th century, which also saw the development of its institutional form. Paintings, sculptures, and the like were classified as “pure art,” and practical or useful endeavors such as crafts, design, or architecture as “applied art.” This division acted as the ground for the authority of “art” as such. While these hierarchies have weakened today, museum collection policies or the established use of the word “craft” (in Japanese) as a bridge between industrial production and fine art show us that the fundamental structures have remained unchanged. Furthermore, since the beginning of the 2000s, ceramics have gained a certain degree of popularity in the art market; as there are rarely any visible steps taken to reflect on the relationship between ceramics and art, however, this trend tends to appear as though collectors are simply consuming these works as products or interior decorations. I believe this echoes a line spoken by the boar god Okkotonushi in the movie Princess Mononoke: “At this rate, we will be hunted as mere meat” (indirect quotation). I do not, however, intend to suggest that ceramics must thus also be presented as “works of art” replete with definite concepts. The real victim of the art market is less ceramics than art itself, the very definition of which grows ever more ambiguous. Neither the artist nor the potter can live without a market for their work, but it would be a mistake to focus solely on sales issues, like who a piece was sold to or how much it was sold for. Artists who keep their distance from the art market are also struggling in a different circuit, where they are trying to get faculty positions at art universities or public grants. Both are cogs in the gigantic art industry.

-

to Shigaraki

Since 2021, I have been making pottery in Shigaraki, one of Japan’s Six Ancient Kilns.

Shigaraki-made “Shigaraki ware” refers to an understated style of stoneware pottery characterized by its scarlet colors, natural ash glaze, and burnt finish derived from firing the high-quality Shigaraki clay in climbing kilns. Shigaraki clay is also well-suited for making large pieces, due to its fire resistance, plasticity, and excellent strength. Shigaraki ware casts itself as “the art of man, earth, and fire,” a sales phrase that points to the uniqueness of an object marked by both the intentionality of human hands and the contingencies of the firing process. In other words, the object’s uniqueness is precisely what makes it valuable. It is the same in painting, where the singularity of an artist’s brush strokes or application of color is especially sought after. Furthermore, it could also be said that what makes art activism art — as opposed to political activism — is precisely its focus, over concrete political achievements, on the failures and difficulties that occur in the process of seeking change for a better society. In other words, the peculiarities and significance that emerge from human intervention have a fundamental underlying value.

The pottery manufacturing industry defines Shigaraki. The proportion of ceramics — dishes, umbrella stands, flowerpots, tanuki figurines — that are mass-produced by large workshops is overwhelmingly higher than the traditional Shigaraki ware made by individual potters. The city itself, too, is overflowing with ceramics, up to its very building materials such as tiles or bricks. While most of Shigaraki’s pottery is indeed mass-produced, about half of this happens through manual labor on the part of its potters. By purposely not automating everything, the system leaves room for each piece to retain its own unique flavor. However, these are distributed not as artwork but as products. While living and making ceramics in Shigaraki, it was made clear to me anew that “creation” is not an act that can be imputed solely to an individual.

On a different note, Ueda and I met in Shigaraki in the fall of 2021. At the time both of us were, for one reason or another, completely tired of life; gradually we became friends who shared our artwork with each other. Not to get overly personal, but I have very few “artist friends,” and Ueda was the first in a long time. However, we are not so close that we keep in constant contact; the only thing we have in common is ceramics. Ueda’s artwork is concentrated less on the qualities conferred by his handiwork and more on the potential of the soil, on taking the contingency of the firing process as far as it will go — that is, in a way it functions as a small laboratory. In fact, the only difference between his clay and his glaze are the ratios of the ingredients. Ueda treats pottery clay, porcelain clay, and glaze as equivalent elements and blends them without discrimination, layering and molding materials with different shrinkage rates and levels of fire resistance as if he were making a mille-feuille. He often collects the soil from the mountains by himself, but he purchases the feldspars and other minerals used in the mix from pottery material manufacturers. Ceramic artists can easily get their hands on small amounts of these materials precisely because the infrastructure for the industry is already in place. In other words, most individual ceramic artists are supported by the surplus generated by the pottery manufacturing industry that creates mass-produced goods. Ueda’s works also feature complex expressive qualities and forms that resemble cooled and hardened lava, but these emerge not from expressionistic impulses but rather from a fusion of the precise calculations of materials engineering and a traditional potter’s intuitions.

The subjects are extremely orthodox — pots, egg-shaped objects, dorodango balls — but, adhering to established earthenware theories at one moment and deviating from them the next, the works he creates have little practical use. By eliminating practicality, the work approaches an objet, stepping into the realm of “pure art.” It could perhaps be said that Ueda’s works have abandoned their practical nature as vessels, and have been optimized as works of art.

By mystifying the artist’s work with words such as “nature” or “fire, earth, and human heart,” we overshadow the infrastructure and the environment that support artists in the pottery and ceramic industries. And in these “SDG” (Sustainable Development Goals)-extolling times, we cannot offer any passable justification for pottery created as impractical “pure art.” This is why it is not good if the artist's urge to create and the desire of the wealthy to buy artwork are the only things that come together to complete the creation of an artwork. In such case, we end up with artwork that is only meant for making money. There is no such thing as equivalent exchange between people, or between a material and the energy that is put into it. The potters of Shigaraki call eccentric objects “hechimon.” This is exactly what Ueda and I create. However, hechimon cannot exist without a legitimate order and substructure. We must not forget that anomalies and kikikaikai (eccentricities) always materialize only in these conditions.”

Yoichi Umetsu

-

Artworks - Yuji Ueda (Selection)

-

Artworks - Yoichi Umetsu (Selection)

-

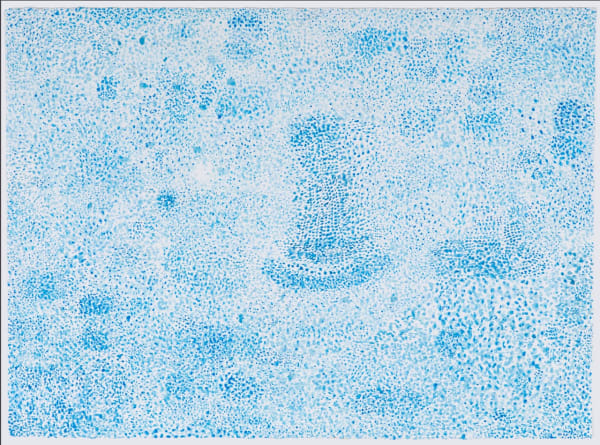

Yoichi Umetsu, クリスタルパレス / Crystal Palace, 2022

Yoichi Umetsu, クリスタルパレス / Crystal Palace, 2022 -

Yoichi Umetsu, ビルボード / Billboard, 2022

Yoichi Umetsu, ビルボード / Billboard, 2022 -

Yoichi Umetsu, ビルボード / Billboard, 2022

Yoichi Umetsu, ビルボード / Billboard, 2022 -

Yoichi Umetsu, ボトルメールシップ / Message Bottle Ship, 2022

Yoichi Umetsu, ボトルメールシップ / Message Bottle Ship, 2022

-

-

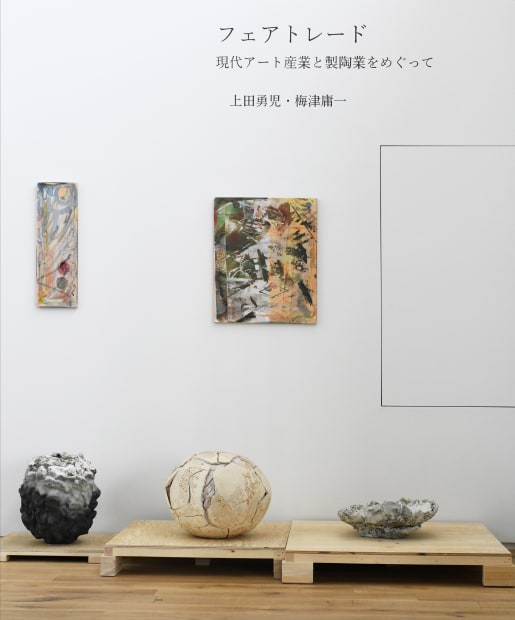

Installation View

-

-

-

Artists Biography

Yuji Ueda

Born in Shiga Prefecture in 1975.

Lives and works in Shigaraki.

Yuji Ueda was born into a family which cultivates Shigaraki’s famous Asamiya tea. He has been making pottery in Shigaraki, one of the Six Ancient Kilns of Japan; since meeting Takashi Murakami around a decade ago, he has primarily exhibited at influential galleries such as Kaikai Kiki. While Ueda’s works draw on the genealogy of traditional pottery, he attempts to foster the potential of his materials to the furthest possible extent. As a result, he creates ceramics that eschew “practicality,” functioning instead as contemporary art objet. His work is well-respected among fellow potters.

Solo Exhibitions (Selection)

2022 "Yuji Ueda Exhibition", The Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo, Japan

2020 "Picking up Seeds", Kaikai Kiki Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2018 "Memories of Soil Cracking Together," Kaikai Kiki Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2012 "Yuji Ueda: Sunaba Exhibition", Sundries Antiques, Tokyo, Japan

Group Exhibitions (Selection)

2021 "Geibi Kakushin", Perrotin, Paris, France

2020 "Healing", Perrotin, Paris, France

2015 "Kazunori Hamana, Yuji Ueda, and Otani Workshop," Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, USA

2012 "Around the 'Kochuten' ", Hidari Zingaro, Tokyo, Japan

Publications

Yuji Ueda: Picking Up Seeds (Kaikai Kiki, 2021)

-

YOICHI UMETSU

Born in Yamagata Prefecture in 1982.

Works at the base in Sagamihara and Shigaraki.

Yoichi Umetsu is an artist who has approached the fundamental questions of “what is art?” and “what is creation?” from a variety of different angles.

He engages in a wide range of activities, including producing paintings and video performance art, as well as running the art collective Parplume, managing a non-profit gallery, engaging in curation, and writing texts. In recent years, he has also set up a base in Shigaraki where he works with ceramics. Last year’s “Art and the Ceramics Industry” event in Shigaraki figured as an attempt to find a connection between its pottery workshop, artists, and local residents.

Solo Exhibitions (Selection)

2022 "Green Sun and Renkon-Shaped Moon", Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2022 “Ceramics and Art", gallery KOHARA and others, Shiga, Japan

2021 "Pollinator", Watari-um Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, Japan

2021 “Heisei Mood", Sokyo Gallery, Kyoto, Japan

2014 "Wisdom, Sensitivity, Affection, A", ARATANIURANO, Tokyo, Japan

Group Exhibitions (Selection)

2023 "World Classroom: Contemporary Art through School Subjects", Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan (upcoming)

2022 "MAM Collection 016: Meditating on Nature - Hisakado Tsuyoshi, Po Po, and Umetsu Yoichi," Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

2021 "Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989–2019”, Kyocera Museum of Art, Kyoto, Japan

2021 “Approaches to Painting – reprise", √K Contemporary, Tokyo, Japan

2020 "Full Frontal, Naked Circulator, curated by Yoichi Umetsu", Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi Main Store, 6F Contemporary Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

2019 "Special Exhibition: Weavers of Worlds - A Century of Flux in Japanese Modern / Contemporary Art”, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

2017 "Parplume University and Yoichi Umetsu”, Watari-um Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, Japan

Publications

ラムからマトン (2015)

Public Collections (selection)

JAPIGOZZI Collection

Takahashi Collection

Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan

Yamagata Museum of Art, Yamagata, Japan

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

-

Artists photo credit: Yuki MoriyaArtworks photo credit: Takahashi Munemasa, office mura photoInstallation view photo credit: Fuyumi Murata, Kanda & OliveiraPlease do not use images without permission

Yuji Ueda, Yoichi Umetsu: Fair Trade - About the contemporary art industry and the ceramic industry

Past viewing_room